How many drinks per week does it take to destroy your liver?

Understanding the most common metric used to quantify drinking levels.

In an article by the founder of Rogue Fitness, P.D. Mangan discusses a story in which he worked in blood banking. He explains that “one consequence of cirrhosis is bleeding, since the liver makes blood clotting factors.” He said he was “fascinated by the fact of hard-core alcoholics needing transfusions. It’s a relatively frequent occurrence.”

One day, he asked a doctor friend who sometimes treated these people how much drinking was necessary for someone to destroy their liver to this level. His reply:

“A bottle of liquor a day for ten years.”

Who could drink that much? As we have pointed out in another article, the drinking habits of the top decile of drinking Americans is an average of 10+ drinks a day. This is just an average though, which means that many people within this group drink significantly more.

Stephen King, one of the most successful American fiction writers of all time—if you know The Shining, It (the clown), or Needful Things… then you know his work. Today, his net worth is $500m+ just from writing. Like many writers, King was a major drinker. One time he was asked by someone if he drank alcohol. He replied: “Of course, I just said I was a writer.”

He described his habits in an interview with the Rolling Stones:

“I started drinking by age 18. I realized I had a problem around the time that Maine became the first state in the nation to pass a returnable-bottle-and-can law. You could no longer just toss the shit away, you saved it, and you turned it in to a recycling center. And nobody in the house drank but me. My wife would have a glass of wine and that was all. So I went in the garage one night, and the trash can that was set aside for beer cans was full to the top. It had been empty the week before. I was drinking, like, a case of beer a night.”

One thing that many people don’t understand is that 10% of Americans live like this. One of the bigger surprises is that generally speaking alcohol consumption and income go hand and hand—it’s not like heavy drinkers are typically people that live under a bridge and don’t work. Heavy drinkers typically aren’t lower class on average, they tend to be middle-to-upper class. Chances are, some of the most successful people you know are in this camp of extreme drinking.

“Heavy drinking” is defined by the US CDC as 1+ drink a day for women (7+ a week) and 2+ drinks a day for men (14+ a week). As can be seen in the chart above, roughly 25% of Americans are “heavy drinkers”. In fact, while 30% of Americans are “drinkers” in the sense that they consume alcohol with any regularity, only about 5% of Americans classify as “moderate drinkers”. Therefore, almost all people that consume alcohol with any regularity are considered “heavy drinkers” and are at a significantly increased risk for liver disease.

This then begs the question… how much alcohol does it take to develop liver disease? As you will find out in this article, the answer isn’t so simple. And thus, people should know the risks and drink with caution.

Some people can live a life of extreme alcohol consumption and never have any liver troubles. An example of this would be Winston Churchill, the famed British prime minister that could be credited with preventing Nazi Germany from taking over the world. It is well documented based on purchase orders to local alcohol distributors that he had about 10+ drinks a day for essentially all of his adult life and lived the age of 90. He was even Prime Minister at the age of 80—albeit, like most 80 year olds, his health wasn’t perfect. His career is regarded as one of the most productive of all time.

On the other hand, some people aren’t so lucky. There are equally just as many cases of people being relatively modest drinkers that go on to develop and die of cirrhosis at a young age.

How many total drinks will to take will it take to destroy your liver?

For many decades, researchers often believed that cirrhosis was the result of a maximum amount of drinks. One of the first studies that took a compelling stab at this was done by a French researcher named Dr. Pequignot in 1970. Pequignot looked in hospitals of 7 French towns with people that had cirrhosis and were closely matched as to sex, age, body weight, and nutritional habits. Through this process he found 381 similar patients that had cirrhosis from what appeared to be primarily stemming from alcohol consumption. 59% of the cirrhotic patients consumed more than 11.4 drinks a day, 37% of them had between 5.7–11.4 drinks a day, and 4% of them had below 5.7 drinks a day. This data is shown above. (Note: A US standard drink contains roughly 14g of pure ethanol. This is 12oz of 5% alcohol beer, 5oz of 12% alcohol wine, and 1.5oz of 40% alcohol spirits.)

Werner Lelbach, a West German researcher specializing in alcohol and liver disease, took this one step further. In 1975 he wrote an article titled: “Cirrhosis in the alcoholic and its relation to the volume of alcohol abuse.” In his research, Lelbach studied West German male subjects in an alcoholism ward to try and determine the amount, lifetime duration, and intensity of drinkers that went on to develop cirrhosis. The people he studied were as follows:

The average amount of daily consumption in Lelbach’s study group was 178.5g of ethanol/day, or about 12–13 American standard drinks a day. The lowest end of people admitted were 2 drinks a day, and the highest end was 33 drinks a day. The average duration of alcohol abuse was 9 years, plus or minus about 6 years. The people in the ward ranged from 19–64 years old.

Lelbach plotted his results along the above curve. Looking at the data found by Pequignot along with his own data, Lelbach concluded that:

If one follows Pequignot’s estimate that a daily intake of 180g of ethanol maintained for roughly 25 years could be considered as an ‘average cirrhogenic dose’, this would correspond to a total intake of about 4200 liters of 100-proof US whiskey at a body weight of 70kg, For the group of German alcoholics presented here, an intake of this size and duration would have been connected with a 50% risk of suffering from cirrhosis of the liver at the end of this period.”

In other words, according to this curve made by Lelbach and Pequignot, about 13 drinks a day for 25 years would give someone a 50% chance of liver disease.

A liter of high proof hard alcohol (50% or “100 proof”) has the equivalent amount of alcohol to 28.125 standard US drinks in total. Using the Lelbach curve, we can use this to then to try and estimate the chances of getting cirrhosis based on a total amounts of lifetime drinks.

- 200,000 drinks = ~100% chance

- 181,000 drinks = ~93% chance

- 163,000 drinks = 89% chance

- 145,000 drinks = 87% chance

- 127,000 drinks = ~82% chance

- 109,000 drinks = ~78% chance

- 91,000 drinks = ~70% chance

- 72,000 drinks = ~63% chance

- 54,000 drinks = ~55% chance

- 36,000 drinks = ~41% chance

- 18,000 drinks = ~18% chance

This above total drinks can then be broken down by time periods and drinks per day. Remember, in Lelbach’s study, the mean duration of alcohol abuse was roughly 9 years.

The above chart is my work in trying to break the Lelbach curve out in terms of drinks per year at different amounts of drinks per day—because of the study’s age, I didn’t have access to the actual curve data and had to eyeball % risk. Obviously, almost anything in the upper righthand quadrant is totally unrealistic—the person would die of alcohol poisoning on day 1—the highest amount of daily consumption in Lelbach’s study cohort was a whopping 33 drinks a day. Equally, the bottom left of the chart seems to be unrealistic as we know of instances of people consuming ~10 drinks a day for ~70 years without being diagnosed of liver disease.

(Note: For a theory on how Churchill did it, other than being extremely lucky and winning the genetic lottery, read our article on the importance of alcohol-free stretches.)

In the beginning of this article we started with the quote of a doctor that often worked with cirrhotics who said that it usually took “a bottle of liquor a day for 10 years” to get cirrhosis. The doctor was likely referring to a “fifth” of hard liquor, which is 17 standard drinks. Based on the Lelbach curve, 17 drinks a day for 10 years puts the user at about a 60% chance of developing cirrhosis. The doctor’s off-the-cuff estimate doesn’t appear to be far off from Lelbach’s analysis.

It may even be spot on considering that recent research appears to show that many people are developing cirrhosis with lesser amounts of alcohol due the fact that human diets and exercise habits continue to get worse, and people are more obese than ever, all of which can lead to liver disease by itself—and is extremely risky when combined with alcohol.

While incredibly interesting, the above chart and analysis is completely unrealistic based on modern data on liver disease and its causes. The idea of asking, “how many total drinks to get cirrhosis?” is the completely wrong question to be asking. Even Lelbach himself recognized this.

Lelbach concluded his analysis by stating:

“A hypothetical calculation of this kind, would, in a strict sense, be applicable only to this group of alcoholics, and reflections of this nature should not be misused to construe, for instance, some sort of ‘formula’ that most certainly would be an unwarranted oversimplification of biological interdependencies.”

As we have discussed in other articles, liver disease is the result of many different factors, including: genetics, BMI, diet, exercise, and even the frequency pattern of alcohol consumption. In fact, many people die of cirrhosis without ever even drinking alcohol.

Therefore, you should expect that for modern people, especially Americans, that we are far more likely to develop end-stage liver disease than the the German males who averaged a weight of just 154 pounds and had a far healthier diet. The average US adult male weighs 198lbs. Which, based on the average adult male height of 5'9", means that the average BMI of Americans is medically obese—which significantly increases risk for liver disease when combined with alcohol. We cover this in an article titled: “You can be a drinker, or you can be overweight, but you can’t be both.”

If the above analysis of “total lifetime drinks” isn’t the right way to look at how your alcohol consumption correlates to risk for liver disease, what is?

Watching your drinks per week—not lifetime consumption.

When you go to the doctor, the most likely question they will ask you about alcohol consumption is: “how many drinks per week do you have?” This is because not only is it the most tracked alcohol-related data point when it comes to drinking, but also the most studied.

In 2019, there was a massive research study published called: “Alcohol drinking patterns and liver cirrhosis risk: analysis of the prospective UK Million Women Study”. In this article, the researchers used data from something called the “Million Women Study”, this was “a prospective study that includes one in every four UK women born between 1935 and 1950, recruited between 1996 and 2001.” The study was primarily conducted in order to study alcohol consumption-related activities and its relative risk for liver cirrhosis. The main questions they asked participants were: “alcohol intake, whether consumption was usually with meals, and number of days per week it was consumed.”

While it is called the “Million Women Study”, only about 40% of the women in the group drank alcohol at least once a week. It was reported:

“During a mean of 15 years (SD 3) of follow-up of 401 806 women with a mean age of 60 years (SD 5), without previous cirrhosis or hepatitis, and who reported drinking at least one alcoholic drink per week, 1560 had a hospital admission with cirrhosis (n=1518) or died from the disease (n=42).”

It should come as no surprise that on average, more drinks per week led to a higher likelihood of liver cirrhosis.

While the chart above isn’t inherently interesting in the sense that it is showing that more alcohol leads to more liver disease, what is interesting about it is the rate at which the risks of cirrhosis increases with each drink per day.

Eyeballing the chart, it appears that “two drinks a day” is roughly 170g of alcohol a week—or 12g drinks, which is about 15% less than American standard drinks. 7 US standard drinks is roughly 100g of alcohol, and 14 is about 200g of alcohol. At 7 US standard drinks a week (100g of alcohol), it appears the risk for developing liver cirrhosis is only about 20–25% greater than not drinking at all (or very seldom—such as 1 drink a week). However, by 14 US standard drinks a week (200g of alcohol), the relative risk for developing liver is about 300% (“3x”) greater. While the chart does not go further, this trend continues upwards with 21 US standard drinks a week (about 300g of alcohol)—this point is confirmed in the chart below on the blue line, as it shows the risks continue to heighten nearly to 28 drinks away before the chart cuts off.

Based on the UK study, it appears that there is quite a bit of logic behind the US CDC recommending that females consume no more than 7 drinks a week.

While the above analysis is for females, it’s a fair speculation that the curve would be similar for UK males, albeit with slightly higher thresholds—especially given that the US CDC recommendation is that males are allowed to have 2x the 7 drinks that females are recommended not to have more than per week.

Another piece of interesting information to come out of the “Million Women Study” study is how weekly drinking patterns, besides just total amount, impacts the likelihood of developing cirrhosis.

As can be seen above, daily alcohol consumption increases the risk for cirrhosis at every point along the curve. In fact, daily drinking is so bad, that the data shows that you would (on average) be better off having 14 drinks a week consumed over 6 or less days than 10 drinks a week consumed throughout each of the 7 days.

Everyday drinking is very problematic from a liver-health perspective. If you’re a drinker, you should avoid it at almost all costs. We deal with this topic at length in an article titled: “Why drinking every day is its own risk factor — and also, one of the easiest things to change to reduce your risks.”

While the above study is the most recent data into how weekly alcohol consumption levels translate to risk for liver disease, one study finalized into a report in 1996 can help fill in the gaps of risk for liver disease at even higher amounts of drinks per week.

In an article titled “Prediction of Risk of Liver Disease by Alcohol Intake, Sex, and Age: A Prospective Population Study”, Becker et al. looked at the associate between self-reported alcohol intake for 13,285 Danish men and women aged 30–79 years old and the risk of future liver disease 12 years later. I.e., they asked people their weekly alcohol consumption amounts between the years of 1976 and 1978, and then waited to see the resulting health outcomes that occurred by 1988. The data of their study can be see in the chart below.

As can be seen in the chart above, the researchers divided the men and women into groups based on amounts of drinks per week, then looked at how many men and women went on to develop liver disease / cirrhosis. As we have more modern results from the UK Million Women study which should be used for women, let’s examine the men more closely here instead.

- 7–13 weekly drinks = 1.8% developed liver disease. (1/56 people)

- 14–27 weekly drinks = 2.4% developed liver disease. (1/42 people)

- 28–41 weekly drinks = 5.3% developed liver disease. (1/19 people)

- 42–69 weekly drinks = 8.8% developed liver disease. (1/11 people)

- 70+ weekly drinks = 11.8% developed liver disease. (1/8 people)

As can be expected, there is a dose-dependent relationship between alcoholic drinks consumed per week and the likelihood of developing liver disease. As mentioned before, this is obvious. However, what is interesting is how much greater amounts of alcohol leads to the risk of developing liver disease. At above 28 drinks a week, the Danish people studied had about a 1/19 chance of developing liver disease roughly 10–12 years later. At above 42 drinks a week, this jumps to about a 1/11 chance. And at 70+ weekly drinks, this is 1/8 people.

Becker et al. did the work of plotting these risk curves for us in the chart above. For whatever reason, after 13 drinks a week, the researchers decided to break out alcohol consumption groups based on 14 drinks/week increments rather than 7 drinks/week. Unfortunately for us, they didn’t give a file containing the data, and thus we don’t have the ability to look at a more granular level than what they presented in their research.

What can be see here is that at 28+ drinks a week for women, the risks increase massively (see the dotted line). The Danish women’s risk for developing liver cirrhosis jumped from about 3.75x (375%) to an enormous 17x (1700%). In men, this also jumps significantly at 28 drinks per week. It goes from about 2x (200%) the normal risk to around 7x (700%). Then from there it increases even more at 42+ drinks a week—13x (1300%). And then goes all the way to 18x (1800%) at 70+ drinks a week.

You may be looking at the above graph and thinking: “Wow, as long as I keep my drinking to under 28 Danish drinks (12g of pure alcohol a pop), my chances of getting liver disease from alcohol aren’t much more than a few times greater than moderate drinking.”

This however is a line of logic that is playing with fire. Modern Americans are far different than Danes of the 70s and 80s.

First of all, 28 Danish drinks is the equivalent of 24 US standard drinks. Second of all, this is studying the deaths of people between 1976 and 1988—who are going to be undoubtedly healthier than Americans in 2020 and onwards. While I cannot find the average height and weight of Danes in their studied time period, I can find it for Americans.

Lelman studied German men in the 1970s. While Germans have gotten less healthy from a BMI perspective over time, they still are significantly healthier based on this metric than Americans. The current average BMI for German males is 25—which is right on the border of “healthy” (18–24 BMI) and “overweight” (25–29 BMI). In contrast, the BMI for the average American male is 28, which is on the high end of overweight and is edging in on an average obese BMI (30–39 BMI).

As can be seen in the chart above, Americans continue to get heavier every year at an alarming rate. As we have pointed out in our article on the risk of being an overweight drinker, it’s estimated that nearly 50% of American adults will be medically obese by 2030. Given that the risks of liver disease compound by around 3x when someone’s BMI is greater than 27 for men and 25 for women, this means that the threshold for drinks per week and its risk for liver disease will most likely be significantly lower than that found in the above Danish study.

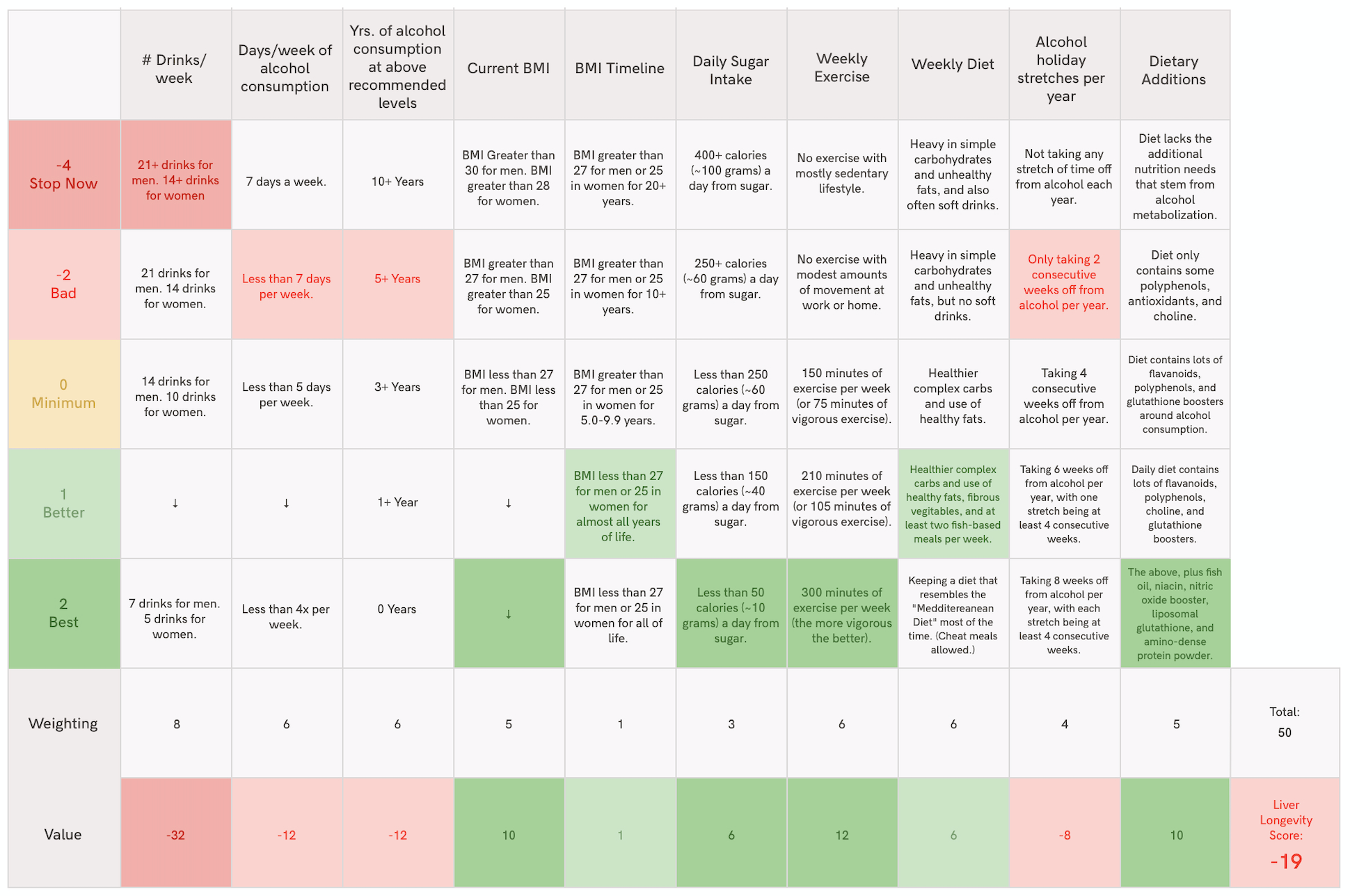

Just like the US CDC recommends, it is ideal that men drink less than 14 drinks a week, and women less than 7. However, if you accidentally drink more (which we don’t recommend), it’s likely imperative that men consume less than 21 drinks a week and women consume less than 14, or else the risk factors most reasonably would skyrocket. (These are the “stop now” levels that we have currently set on the Liver Habits Score.)

In summary: more alcohol per week = greater risk for liver disease.

It’s important to understand that the above research articles are merely the tip of the iceberg when it comes trying to estimate the risk of different levels of alcohol consumption. What we have done here is taken a number of representative studies and used them to explain the concept of how more alcohol consumption leads to greater risk for developing liver disease.

One debate that is still present in the the academic literature is whether alcohol’s influence on risk for liver disease is “dose dependent” or has a “threshold effect”. Dose dependent would mean that as more alcohol is consumed the risk goes up. A threshold effect would mean that the risk for liver disease increases at a specific threshold—such as at a specific number of drinks per week. One example of this would be another Danish study in which researchers found that after ~30 US drinks a week, the risk for liver disease remained about the same. (I.e., someone isn’t at more risk if they consumed 45 US standard drinks a week vs 35 drinks a week.)

Our thesis based on what we have seen is that it’s likely a mixture of both, and that when it comes to making health-related decisions, it’s important to keep both in mind. For example, if there is indeed a threshold effect, that is a moot point in the sense that the recommendation would still be to drink less alcohol to get under that threshold. And then, below that threshold, as seen with the UK Million Women Study, alcohol is still going to have a dose-dependent correlation to risk. Therefore, we are strong believers in understanding that at its core, alcohol consumption quantity and liver disease risk are inextricably tied together.

While Lelbach and Pequignot tried to quantify a total amount of alcohol that it takes on average to destroy a person’s liver (“‘average cirrhogenic dose”), modern research has shown that this is the wrong way to look at it. A 2014 study published in The Journal of Hepatology titled “Alcohol drinking pattern and risk of alcoholic liver cirrhosis: a prospective cohort study” ended with the following conclusion:

“Recent alcohol consumption rather than earlier in life was associated with risk of alcoholic cirrhosis.”

Therefore, while it’s not unimportant to understand someone’s prior alcohol consumption habits (indeed, some studies have shown connections between earlier in life alcohol consumption and liver health outcomes—even if the person stopped drinking entirely)… arguably the most important statistic to look at is recent alcohol consumption quantities. Hence why your doctor asks: “how many alcoholic beverages do you consume per week?”

If making sure your liver is going to last your throughout this many decade long journey called life is important to you, then you should do everything you can to reduce your number of weekly drinks—preferably to under 14 drinks a week for men, 7 for women, and definitely not more than 21 drinks a week for men or 14 for women. And almost as importantly, to ensure you don’t drink every day.

The liver is an amazing organ in its ability to regenerate and heal itself. Therefore, even if you’ve put it through the grinder like I have throughout my years, it is never too late to adopt liver-healthy habits, such as promoted through our Liver Habits Score.

Skål! (“Cheers” in Old Norse—it comes from the word “bowl” that alcohol was often drank from. It’s used primarily in Danish, Swedish, and Norwegian as a customary toast before consuming alcohol.)

Brooks Powell, Founder of Cheers.